On March 22, Global News had a scoop headlined: “Liberal MP Han Dong secretly advised Chinese diplomat in 2021 to delay freeing Two Michaels: sources.”[1] The story was based on statements from two “separate” unnamed “national security” sources. Not much was said in the piece about the sources and their motives for going public two years after the fact. Neither do we learn anything compelling about their vantage point. Key quotes are indirect and attributed to both sources. The story may be true, perhaps unimpeachable, but Dong, who has now left the Liberal caucus, says it is false, and others have raised valid questions and expressed doubts[2]. Dong’s denials duly appear in the story, and he claims that he called for the “immediate release” of the two prisoners. Dong now wants to sue Global News to “clear his name.” Are we in for another sequel in the perennial Anonymous Sources Saga?

Global News stands by its reporting and told the Globe and Mail in an email: “Global News is governed by a rigorous set of Journalistic Principles and Practices and we are very mindful of the public interest and legal responsibility of this important accountability reporting.”[3] Global News guidelines relating to “confidential sources” are among the most concise you can find[4].

If the story is indeed shown to be flawed, will the sources’ identity be revealed? Will the media be accused of sloppy reporting? Years will pass before we get answers (if we do), but one thing is certain: Global News would be in a much more comfortable position today if its sources had been named.

But anonymity is now the name of the news game. It has become so ubiquitous, offered on a silver platter to sources who only need to timidly whisper they “prefer” to remain unidentified, that reporters have now painted themselves in a corner. The mass of precedents has made refusing anonymity “requests” very difficult. Anonymity is routinely granted, and there is no putting back the toothpaste in the tube unless editors have an unlikely Road of Damascus collective experience. Some, in the media, even suggest that sources be identified when conditions allow, turning the widely-accepted “anonymity as last resort” principle on its head.

Case in point, see this article in the New York Times, which I noticed as I was writing this blogpost: “Kushner Firm Got Hundreds of Millions From 2 Persian Gulf Nations.” The substance of the piece is attributed to “people with knowledge of the transactions—in other words, people who are aware of what they are advancing. It’s not even clear how many sources were involved[5].

“It was cool to use [anonymous sources] in the 1970s because of [Watergate reporters] Woodward and Bernstein. But 1981 was a watershed year after the Janet Cooke [fabrication] case. Every journalism publication came out with these long essays saying we can’t use anonymous sources anymore… Everyone beat their breast and said we are going to do better. But I don’t think anything really changed.” Theodore L. Glasser, then director of Stanford University’s journalism program, said that in 1994[6].

Glasser misread the situation. Things were changing. But they were not moving in the direction he wished. In the following decades, anonymity spread faster than a coronavirus variant in a retirement home. And in 2022, Margaret Sullivan, formerly the public editor of The New York Times, who had valiantly crusaded against the abuse of blind quotes, could write that “far from being treated as a last resort, anonymity [is] being handed out as generously as Snickers bars on Halloween…”[7]

It will perhaps be surprising for some readers to learn that, according to professional norms, naming sources is the standard[8] and that anonymity is supposed to be the exception, a “last resort” reserved for special situations—a privilege, as The Globe and Mails calls it, to be reluctantly conceded to obtain game-changing information. “There should be only rare and well defined exceptions to the rule that a journalist always reveals his sources; secrecy and journalism are contradictions in terms.”[9]

The daily tsunami of unidentified, unnamed, confidential or anonymous sources[10], who in most cases provide only mundane, run-of-the-mill, predictable, low-impact information or comments, or, quite simply, allegations and rumors, flies in the face of the restrictions, standards and precautionary guidelines designed and promoted by the press itself and found in journalism textbooks or editorial codes. The said guidelines emerged mostly in the 1980s. They were tightened in the wake of the 2003 Jayson Blair fabrication affair and other scandals[11], to no discernible effect. In a sample of just six editions of The New York Times, in 2007, researchers found no less than 238 anonymous sources: 79% of them did not comply with internal rules, 42% expressed opinions, 47% provided uncorroborated claims[12].

Today, we are left with an abysmal gap, in the press at large, that separate what newsrooms, press councils, journalist associations, scholars and veteran reporters preach, and what actually gets published or aired. And anonymity handed out as “Snickers bars” explains in part why the press has lost so much credibility over the last 50 years. High time to walk on the paint. It’s pretty dry, anyways.

For starters, why do we expect quotations in news stories?

Obviously, some stories could not exist without mentioning and quoting sources. Statements, announcements, pronouncements, demonstrations—numerous news stories are triggered by “newsmakers” who orchestrate “PR operations” that get the press gears moving. Journalists convey the “message” to the public, but we also expect them to perform additional research and seek “reactions” from additional sources to provide perspective and context—that’s called reporting. In such cases, emitters and commentators are inseparable from the core of the story. Similarly, it is difficult to imagine “controversy” and “conflict” stories without sources being mentioned and eventually quoted.

But in other stories, reporters face no strict obligation to quote or even identify sources. For sure, they have no obligation to mention and quote all their sources, which would in many cases be impractical and confusing. Yet, most stories contain attributed information or comment, for example expert or witness opinion, generally considered and presented as substantive. Indeed, many stories are built around such quotes.

Quotes make news stories livelier, more attractive, more authentic. They make a reporter’s work stand apart, by providing color and depth to a story that would otherwise amount to commodity news. But those are not the only reasons explaining the systematic recourse to quotes, now a well-established convention in news reporting. Another is the “call for objectivity.” In the name of impartiality and for the sake of neutrality, reporters are instructed to keep their opinions in check and refrain from expressing personal value judgments. But it’s difficult, perhaps impossible, to make a story comprehensible by just aligning cold facts. Value judgments are inevitable, but we expect them to come in large part not from reporters, but from story participants, stakeholders, witnesses, people “in the know”—and also, importantly, from independent observers and experts who will make the story more authoritative. Textbook authors Lanson and Stephens write: “A reporter, guarding a reputation as an unbiased observer, must attribute any opinions, any subjective comments, that appear in a news story.”[13]

But noting that sources and quotations are inevitably and carefully selected and qualified by journalists, sociologist Gaye Tuchman famously suggested that quotes, especially direct quotes, are a feature of what she called a “strategic ritual” to which reporters adhere to appear objective. According to that view, journalists use quotes to give the impression that they have removed themselves from the story. The said ritual, in other words, would imply little benefits other than protecting the reporter from criticism by providing cover. Tuchman wrote: “[Journalists] view quotations of other people’s opinion as a form of supporting evidence. By interjecting someone else’s opinion, they believe they are removing themselves from participation in the story, and they are letting the ‘facts’ speak.”[14] Hence, genuine “objectivity” is very much dependent on the relevance of sources and quotes, as well as on the reporter’s overture to opinions or versions he or she doesn’t agree with.

I won’t expand here on the hot-potato concept of objectivity. But I would suggest you read two recent, excellent pieces on that topic, especially if you are a member of the objectivity-does-not-exist crowd: “Journalistic objectivity is an ideal worth defending,” by Toronto Star columnist Andrew Phillips, and “We want objective judges and doctors. Why not journalists too?” an op-ed by ex-Washington Post and ex-Boston Globe Martin Baron.[15]

Another major factor behind the presence of sources and quotes in the news relates to a different concept: transparency. More than ever, the public expects to know how the reporter has come to learn or confirm the information presented as a pivotal morsel of truth. Attribution makes clear where a fact or an assertion comes from (official statement, human source, document, media report, etc.). And in the case of human sources, journalists are invited to describe the source’s credentials, thus putting the audience in a position to make a judgment about its credibility and the value of the information. Authors Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel wrote: “In journalism, only by explaining how we know what we know can we approximate this idea of people being able, if they were of a mind to, to replicate the reporting. This is what is meant by objectivity of method in science, or in journalism.”[16]

Why is not naming sources a problem? Why the fuss?

The short answer is that quoting named sources makes the media, the reporter and the story more credible. And not naming sources does the opposite. A public editor of The New York Times once said that anonymous sourcing was the main media credibility killer.”[17] According to Bloomberg News “the best writing depends on authoritative attribution, or documentation of what is said and done. Attribution helps define a good story because we are the agents of our readers, not our sources. That means we have an obligation to be precise about who said what and under what circumstances. Readers have far more confidence in stories that provide opinions uttered by recognized people and media than stories without attribution.”[18]

Can “newsmakers” remain anonymous? Deborah Howell, who had a long career in journalism, including as ombudsman of the Washington Post (2005-2008), promoted the following rule: never use an anonymous source as the first quote in a story[19]. Indeed, basing a report on an anonymous statement, even if the story is right, makes it appear suspect. In other words, the sheer recourse to anonymity raises doubts, it sprays the story with the perfume of fabrication.

Howell would be disappointed at the current state of affairs. Anonymous comments and “truth-claims” are often a story’s cornerstone, splashed in leads, and even in headlines, sometimes in the plural form to leave the impression of multiple sources saying something similar. “Sources familiar with the situation say…” and “critics say…” represent a suspicious and risky, yet very popular story template. And what unnamed “critics” say sometimes amounts to a value judgment that the story editors happened to like very much (this by pure coincidence, of course).

In the Global News’ Dong piece, both the lead and the headline were attributed to the unidentified sources, and caveats made the core of the story unclear: “Liberal MP Han Dong, who is at the centre of Chinese influence allegations, privately advised a senior Chinese diplomat in February 2021 that Beijing should hold off freeing Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, according to two separate national security sources.” Should readers conclude that the reporter had been unable to confirm this was true? Or is the reporter simply repeating what the sources contend?

And then: “Both sources said Dong allegedly suggested to Han Tao, China’s consul general in Toronto, that if Beijing released the ‘Two Michaels,’ whom China accused of espionage, the Opposition Conservatives would benefit.” Allegedly? Suggested?

Was this a factual story, or just speculation and innuendo from two unnamed sources? Was this simply the story of two sources rehashing unproven hearsay? What did the sources say, precisely? How did they know what they appear to say they know?

“The two traditional culprits for relying on anonymous sources are lazy reporters and competition. Sometimes it’s hard getting a source to go on the record. You may have to call more than one person. You may have to put down the phone and knock on a door. Sometimes the story is hard to write without the key quote, the quote that says what you need it to say, but no one will go on the record with it. So you call up someone who sees it as you do and offer anonymity—and get the quote you need. It ain’t right—but it’s done,” says John Christie, co-founder of the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting.[20]

The obvious problem is that certain sources could say about anything once they know their identity will be kept from view and they can avoid accountability until the end of times. Anonymity makes sources influential and powerful, it invites exaggeration and recklessness. Sources can settle scores, use hyperbolic language they would never use on the record, gild the lily, cut corners, omit or distort key facts—inadvertently or not. In short, sources are not always right, competent, objective, prudent, and disinterested. But when named, at least, they are accountable. “The problem isn’t that there’s something morally wrong with people being off the record. The problem is that that relationship has been converted from a tool that we offered to sources who were reluctant to provide us with information into a device that sources use to manipulate us,” Kovach and Rosenstiel wrote.[21] I also suspect that sources who want to be helpful sometimes speculate, and that, to their astonishment, their speculations morph into facts or allegations in the published story. Sources can be tricked, and there is not much they can do about it if they refused to be named. “Reporters can use anonymity, at its extreme, as dishonestly as their sources do, inventing stories nearly impossible to verify or discredit,” wrote journalist and author Steven Weinberg[22]. And the public knows it.

Bottom line, reporters are more credible when they are clear about where information comes from, and when opinions and comments are clearly attributed. The public can then make a judgment about newsmakers and commentators, and sources can speak up if their quotes are distorted or not fairly presented. Otherwise, “[readers] don’t know who is speaking so they can’t trust it, they can’t tell if it is real or made up, they can’t tell if the source has an agenda or is even knowledgeable […] We ask to be trusted—and then over and over again give readers reasons to do the opposite,” wrote John Christie[23].

Granting sources anonymity is sometimes vital, but I am not sure all journalists understand the Faustian deal anonymity agreements imply. The spirit of journalism ethics is clear: when anonymity has been granted, both the source and what the source said are considered to have been carefully vetted by the reporter, and the responsibility of both journalist and media is fully engaged. There is no “blame-it-on-the-source” off-ramp. Named sources publicly bear responsibility for what they say. Unidentified sources don’t, because the reporter and the media shoulder it. “The bottom line is that journalists should not print information by anonymous sources unless they are completely convinced it is true, for it is the reputation of the journalist—not the source—that is on the line,” wrote veteran journalist and professor Kelly Toughill[24]. I would add that conveying allegations or innuendo attributed to unnamed sources has nothing to do with “enlightening the public” and much to do, in many cases, with “spreading rumors.”

Background Sources

It may appear a paradox, given the above, but numerous sources remain invisible, and that’s perfectly fine. As mentioned earlier, reporters have no obligation to list or quote all their sources. As “truth-seekers” (to use vocabulary proposed by Kovach and Rosenstiel[25]), they first and foremost chase information or hints, not quotes, and they are eager for anything useful coming from any trusted source in a position to know, including stuff provided “off-the-record” or on “background.” The “naming and quoting” issue only arises at the “truth-presenting” stage, and it may not arise at all: “Verified facts need no attribution,” says the Globe and Mail‘s Editorial Code of Conduct, rightly.

Bloomberg News once put it this way: “Never stop talking to those in the know. We can use the insights of people who insist on anonymity as fodder for the less-informed who are receptive to publicity.”[26] In short, there is no blanket obligation to name or enumerate corroborative sources, or to attribute every bit of factual information, and a request for anonymity is no reason to slam the door on a source, or ignore what it has to say.

In investigative reporting, the infamous, oft-quoted Woodward and Bernstein “two-source rule” means at least two additional, independent sources are required before publishing any key information that came from an original source (identified or not). Veteran investigative reporter and author John Ullmann thinks that so-called “rule” is “total bullshit… It could be that you should be satisfied with one [source], or it could be that you shouldn’t be satisfied until you have fifteen.”[27] I don’t think I would betray Ullmann’s thinking by adding that sometimes, fifteen is not enough. Hundreds of people would happily “corroborate” that Joe Biden stole the 2020 presidential election to Donald Trump—it does not make it true.

The scope of the corroboration process varies depending on context. What counts, in the end, is not the number of sources (named or not), but gaining reasonable assurance that the information is valid. Much depends on the credibility and vantage point of the various sources. No two cases are identical, it’s a matter of professional judgment, circumstances, and common sense.

Corroboration entails two distinct, complementary approaches, both vitally important. The first, as described above, is to find sources (human or documentary) confirming what an original source has said. If human, such corroborative sources must be independent from one another, not connected in any way, to avoid and eventually eliminate any risk of source contamination[28] (Was that the case for the Dong story?). The second approach, often overlooked, but essential, is to actively seek sources who could possibly disconfirm, refute, alter or nuance what other sources said—a process sometimes referred to as “testing information,” which could also be dubbed “testing sources” (In the the Dong story, CSIS refused to confirm or deny).

Truth-seeking reporters strive in an almost maniacal way to speak to anyone in a position to know. They want to actively hunt down inconsistencies—not do everything they can to avoid them (or worst, cover them up). They do not declare “mission accomplished” the minute they get a handful of confirming quotes, especially when said quotes come from untried sources. “We must work just as hard on the antithesis as we do on the thesis,” writes John Ullmann[29]. Reuters has made this a formal guideline: “When doing initiative reporting, try to disprove as well as prove your story.”

So “transparency” is paramount, but it does not mean reporters must describe the minutiae of everything they did to accomplish their mission of “verification.” If corroborative sources want to speak on background only, so be it—that’s not in itself a problem. In fact, readers should perhaps be suspicious of stories that insist heavily on the existence of multiple corroborative sources, especially if unnamed: it may be the sign that the reporter has not genuinely ascertained the facts and hopes to be in a position to pin responsibility on sources if the story crashes.

Steve Weinberg, who fingerpointed Bob Woodward for his overuse of anonymous sources, wrote: “I will continue to listen to sources who speak off-the-record, on background, not for attribution. Unlike Woodward, I will usually decline to pour their unattributed words into my books and articles. I will try to find other sources just as knowledgeable who will speak for attribution. I will search the paper trail for confirming documents. If I fail on the people and the paper trails, I will probably never publish the information.”[30]

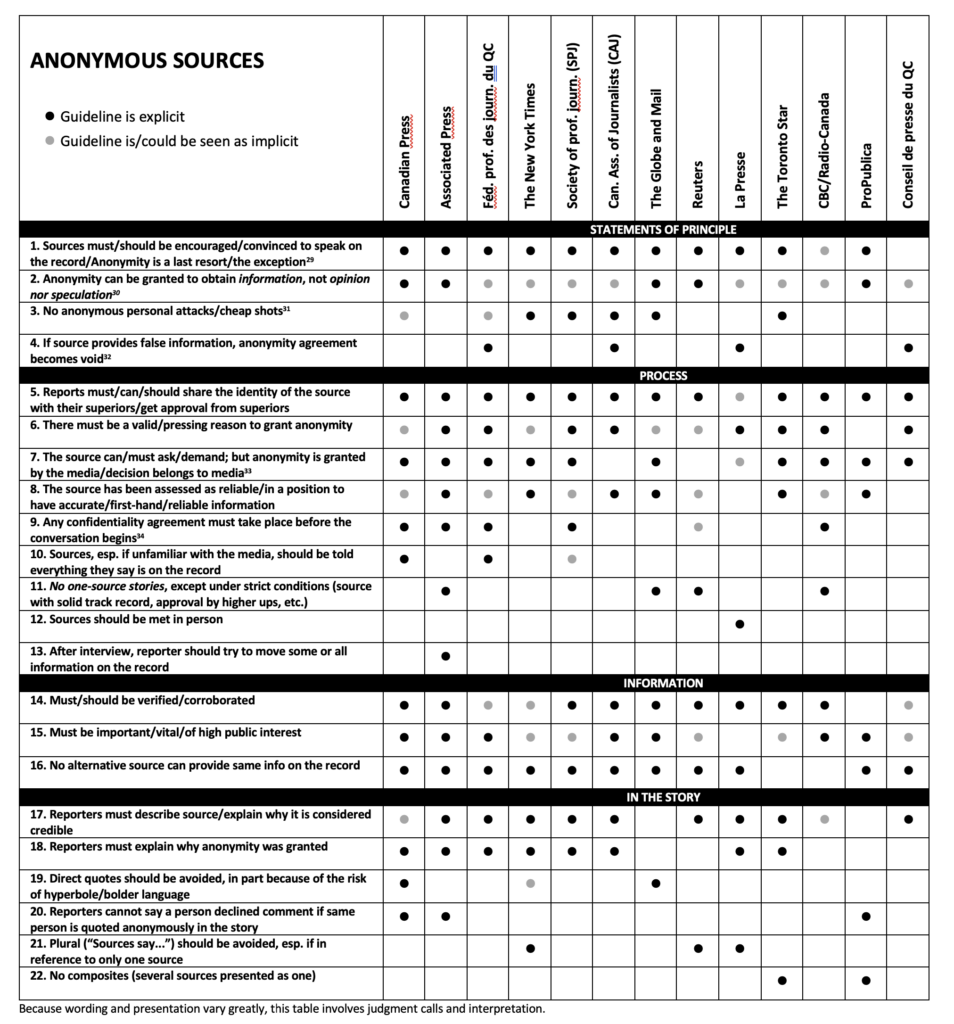

The Guidelines

The following table is a comparison of various sets of guidelines on anonymous sources. Some are detailed and unambiguous, others are elliptic, sometimes bordering on the nebulous. But taken as a whole, the picture is fairly consistent: anonymity should be granted in certain circumstances only, at certain conditions only, and only for conveying information—not opinion or personal attacks; the source, especially if previously unknown to the reporter, should be carefully vetted; and the information supplied by the source should be corroborated, unless it is spectacularly important and comes from a source with an established track record; the public deserves explanations about the source (why is it considered credible?) and the (presumably valid) reason for which anonymity was granted. The wording of the guidelines varies greatly, but they have one thing in common: they are not enforced. They are window-dressing.

SOURCES

Canadian Press: The Canadian Press Stylebook, 17th edition (2013). See also March 6, 2019 CP statement following an article by Rabson, M.: https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2019/02/09/wilson-raybould-entered-federal-politics-hoping-to-be-a-bridge-builder.html

Associated Press: The Associated Press Stylebook, 2013, p. 315-316, double-checked against the rules found online Jan. 2023.

Fédération professionnelle des journalistes du Québec: Guide de déontologie, sections 3a; 4b; 5b; 6.

The New York Times: NYT Manual of Style and Usage, 5th edition (2015); Guidelines on integrity, as revised September 25, 2008; How The Times Uses Anonymous Sources, by Phillip B. Corbett, standards editor, June 14, 2018; Internal memo of August 31, 2010, by Corbett: A Reminder on Anonymous Sources—See: https://www.gawker.com/5627330/new-york-times-warns-newsroom-on-anonymous-sources

Society of Professional Journalists: Code of Ethics; Position paper on anonymous sources, by Michael Farrell, Ph.D., director of the Scripps Howard First Amendment Center, University of Kentucky, associate professor of journalism, for the SPJ Ethics Committee (no date); SPJ,Media Ethics, A Guide for Professional Conduct, 5th ed. revised by F. Brown and SPJ’s Ethics Committee, 2020, p. 196.

Canadian Association of Journalists: Ethics Guidelines; Statement of Principles for Investigative Journalism, 2004.

The Globe and Mail: Editorial Code of Conduct, updated 2022, retrieved online Jan. 2023.

Reuters: Reuters Standards and Values, consulted online, January 2023.

La Presse: Guide des normes et pratiques journalistiques de La Presse, available online.

Toronto Star: Torstar Journalistic Standards Guide, 2018 (current as of Jan. 2023). See also https://www.thestar.com/opinion/public_editor/2019/03/07/we-must-maintain-the-highest-standards-on-using-unnamed-sources.html

CBC/Radio-Canada: Journalistic Standards and Practices, consulted online, Jan. 2023.

ProPublica: Code of Ethics (retrieved online, Jan. 2023).

Conseil de presse du Québec: Guide de déontologie du Conseil de presse du Québec.

[1] Cooper, S., Liberal MP Han Dong secretly advised Chinese diplomat in 2021 to delay freeing Two Michaels: sources, Global News, March 22, 2023.

[2] See Mastracci, D., I Don’t Trust Global News’Reporting on Han Dong, Passage, March 23, 2023. See also Fife, R. and Chase, S., Trudeau government decided CSIS transcript of MP Han Dong provided no ‘actionable evidence,’ The Globe and Mail, March 23, 2023.

[3] See Fife, R. and Chase, S., op. cit. See also Berthiaume, L., Han Dong threatens legal action against Global News over foreign interference report, Canadian Press, March 27, 2023.

[4] “[Journalists should] use confidential sources only when there is overriding public interest and when sources legitimately require their identities be concealed. When we do grant anonymity, we will disclose to the audience why we have done so.”

[5] Swan, J., Kelly, K., Haberman, M., and Mazzetti, M., Kushner Firm Got Hundreds of Millions From 2 Persian Gulf Nations, New York Times, March 30, 2023.

[6] Shepard, A. C., Anonymous Sources, American Journalism Review, December 1994.

[7] Sullivan, M., Newsroom Confidential, St-Martin’s Press, 2022, p. 75.

[8] Bernier, M.-F., Éthique et déontologie du journalisme, Presses de l’Université Laval, 2004, p. 257.

[9] Adler, R. quoted in Goodwin, H. E., Groping for Ethics in Journalism, Iowa State University Press, 1987, p. 118.

[10] Those terms are synonymous. Anonymous sources, whose identity is known to reporters, should not be confused with anonymous tipsters, informants or whistleblowers who do not identify themselves.

[11] Duffy, M., Anonymous Sources: A Historical Review of the Norms Surrounding Their Use, American Journalism, 31 (2), 2014.

[12] Lizaire, C. and Tejada II, A., About Those Anonymice, Columbia Journalism Review, October 2008.

[13] Lanson J. and Stephens, M., Writing and Reporting the News, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 92.

[14] In Objectivity as Strategic Ritual: An Examination of Newsmen’s Notions of Objectivity, The American Journal of Sociology, 77 (4), January 1972, p. 668. See also Tuchman, G. Making News, A Study in the Construction of Reality, The Free Press, 1978, p. 95.

[15] Phillips, A., Journalistic objectivity is an ideal worth defending, Toronto Star, March 28, 2023. Baron, M., Opinion: We want objective judges and doctors. Why not journalists, too? Washington Post, March 24, 2023.

[16] Kovach, B. and Rosenstiel, T., Journalism of Verification, in Adam, G. S. and Clark, R. P., Journalism, The Democratic Craft, Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 178.

[17] Paraphrased from Dan Okrent, in Preserving Our Readers’s Trust, A Report to the Executive Editor, May 2, 2005.

[18] Winkler M. and Wilson, D., The Bloomberg Way, A Guide for Reporters and Editors, 10th edition, Bloomberg News, 1998.

[19] Kovach, B. and Rosenstiel, T., Journalism of Verification, op. cit., p. 184.

[20] Christie, J., Anonymous sources: leaving journalism’s false god behind, Poynter Institute, April 23, 2014.

[21] Kovach, B. and Rosenstiel, T., Sources: Have Journalists Ceded Control?, Nieman Report, Spring 2001.

[22] Weinberg, S., The Secret Sharer, Mother Jones, May 1992, p. 55.

[23] Christie, J., op. cit.

[24] Toughill, K., The perils of anonymous sources, Toronto Star, Feb. 3, 2007.

[25] Kovach B. and Rosenstiel, T., The Elements of Journalism, Three Rivers Press, 2001.

[26] Winkler M. and Wilson, D., The Bloomberg Way, op. cit.

[27] Quoted in Ettema, J. S. and Glasser, T. L., Custodians of Conscience, Investigative Journalism and Public Virtue, Columbia University Press, 1998, p. 49.

[28] Ettema and Glasser, op. cit., also elaborate on “structural” (several “facts” making a story coherent) and “multiplicative” corroboration (several stories showing a pattern), see p. 139-143.

[29] Ullmann, J., Investigative Reporting, Advanced Methods and Techniques, St-Martin’s Press, 1995, p. 38.

[30] Weinberg, S., The Secret Sharer, op. cit., p. 59.

[31] In his PBS set of guidelines, Jim Lehrer wrote: Do not use anonymous sources or blind quotes, except on rare and monumental occasions.

[32] See also Anonymous Sources: Factors to consider in using them […], a 2013 blogpost by journalist Steve Buttry. He wrote: “I can’t imagine why a journalist would publish opinions, especially critical opinions, from an unnamed source. If a source gives you information, you can seek documentation or verification from other sources […] But the value of an opinion is entirely dependent on the person holding the opinion.”

[33] “Never allow a source to engage in anonymous attacks on other individuals or groups. Anonymous attacks risk involving you and your employer in a libel suit and are inherently unfair to the person attacked” (Bender, J. R. & al. Reporting for the media, Canadian edition, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 172); “We do not provide anonymity to those who attack individuals or organizations or engage in speculation—the unattributed cheap shot. People under attack in our publications have the right to know their accusers.” (Toronto Star, Journalistic Principles). According to Duffy, M., op. cit., “by the late 2000s… most news organizations and textbooks prohibited the use of anonymous sources to wage personal attacks.” (p. 261) The challenge, I suspect, resides in determining where to draw the line between “cheap shot” and “fair comment” in a society that values “free speech.” In his PBS set of guidelines, Jim Lehrer wrote: No one should ever be allowed to attack another anonymously.

[34] In 2001, in The Elements (op. cit.), Kovach and Rosenstiel wrote (p. 82): “A growing number of journalists believe that if a source who has been granted anonymity is found to have misled the reporter, the source’s identity should be revealed. Part of the bargain of anonymity is truthfulness.” Seasoned Canadian journalist “Andrew Mitrovica […] says that a journalist has a responsibility to reveal, not defend, a confidential source if it becomes clear that the potentially damaging information they were given was false […] ‘Far too often the fourth estate doesn’t hold itself to the same measure of accountability and transparency that it does other powerful institutions’ [says Mitrovica].” (See Sifton, B., A right to protect? The confidential source controversy in journalism, Center for Journalism Ethics, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Wisconsin-Madison, June 9, 2008). See also Supreme Court of Canada, R. v. National Post 2010 SCC 16, paragraphs 5, 30. “The courts understand the need in appropriate circumstances to protect from disclosure the identity of secret sources who provide the media, on condition of confidentiality, with information of public interest, but even the journalist Andrew McIntosh recognized that if his source had provided the document ‘to deliberately mislead me’ the source would no longer be worthy of protection.”

[35] For more, see Goodwin, op. cit. p. 119s.

[36] See also Lanson J. and Stephens M., op. cit, p. 237, 241 (“Ground rules should be agreed upon before information is exchanged”); Ullmann, J., op. cit., p. 48; Sormany, P. Le métier de journaliste, 3e ed., Boréal, 2011, p. 206.